|

About a dozen years ago I was helping my mom with something in the basement when I asked her about the wedding portraits. Two very large photographs of each of my great-grandparents had hung in the basement since my grandma went into the nursing home, their ornate nineteenth-century frames clashing madly with the room's plywood walls. "Have you thought about what you'll do with these?" I asked, my scholar's eye snapping into focus. "They really should be preserved." My mom nodded, adding, "You know the secret of these, don't you?" "What?" I asked. (We are not a family with very many secrets.) "Their heads were put on other people's bodies."

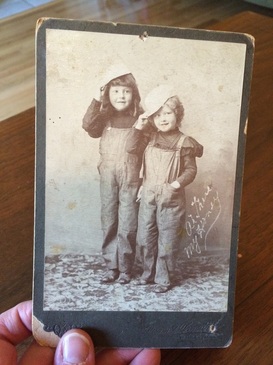

My eyes got wide and I looked at the images anew: overpainting. Of course! A common practice of the late nineteenth century where the photographed heads of customers were superimposed on other bodies (usually better-dressed ones) in a kind of early Photoshop manuever. Overpainting allowed people like my great-grandparents, newly-married in the late 1880s, to make themselves look a little better than they were, to communicate their aspirations visually. I wrote about these portraits when I started working on the article that would eventually become chapter two of Making Photography Matter. They are perfect examples of how by the late nineteenth century, the perceived relationship between photographic portraiture and human character was so implicitly well-understood that even a young couple just starting out in Kilbourne City, Wisconsin knew the score. The Finnegan family archive came in handy again in chapter three, which examines how visual fictions of childhood structured the debate about child labor in the U.S. The chapter opens with the cabinet card above, featuring my grandmother, Isabel Chase Finnegan (left) and her sister, Edna Chase Lewis. (Their parents are the ones in the wedding portraits.) Here's what I say about this image in the book: Undated but likely made at the turn of the century in a northern Minnesota frontier town, the studio portrait finds the Chase sisters engaged in a bit of cross-dressing and role-playing. Isabel and Edna are dressed identically in dark blouses and overalls, white caps placed jauntily at an angle on heads full of carefully tended ringlets. . . . Their costumed bodies offer the viewer two beloved little girls playing dress-up, masquerading to the camera as happy little worker boys. Clearly no one is fooling anyone; one would never mistake these girls for the laborers whose costumes they have put on. Not child laborers but children dressed as laborers, in this portrait the Chase girls are playfully yet squarely positioned within the sentimental frame of the sacred child (Making Photography Matter, p. 83). Later in the chapter I contrast this family image with a photograph of actual child laborers made in a photographic studio not unlike the one in which the Chase girls were photographed. Titled "A Bit of Realism," this second photograph was published in American Federationist magazine in 1902. Featuring anti-child labor activist and writer Irene Ashby-Macfayden posing maternally with three barefoot child laborers, the image appropriates "the formal, familial setting of the conventional portrait studio" in order to challenge the magazine's readers to "see child laborers as valuable, significant, and worthy" (p. 97). Without the repeated circulation of visual fictions like those performed by my grandmother and her sister, this activist image would likely have made little sense to audiences. As it was, it served as a powerful reminder that not all children got to merely play at labor. How do family photos function as photo history? For me, what makes them powerful is that, when properly contextualized within the history of the medium, they serve as concrete illustrations of changing social and cultural practices and norms, providing an almost embodied insight into the ways we make photography matter. Here, I can say. This is my grandmother as a child. I remember her as an old woman, working in her garden, and I used to sit on her lap. Yet I can also say, my grandmother and her sister represent a way of seeing children that had a powerful rhetorical impact in its time. That matters to me too.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

ABOUTResearch news, commentary on visual politics, and a few old blog posts given new life. Archives

January 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed