It's been a busy few weeks for Making Photography Matter. In mid-November I learned that the Visual Communication division of the National Communication Association named it "Outstanding Book of the Year." This is an especially meaningful honor because the Visual Comm division was the very first thing I joined when I became a member of NCA twenty years ago. For them to honor my work all these years later makes me feel really good (and, truth be told, really old). Thank you, Vis Comm!

In other MPM news, last week I was interviewed by communication/rhetoric scholar Karma Chavez on Madison radio station WORT's program "A Public Affair." It was a fun, wide-ranging conversation about several topics, including Civil War photography, rhetorical methods, why 19th century Americans were obsessed with Abraham Lincoln, and what my students have taught me about selfies. You can listen to the interview here.

0 Comments

A couple of weeks ago, the good folks at the Chicago Humanities Festival announced their lineup for the 2015 event, which will take place from Oct. 24 through Nov. 8. And I'm thrilled to be on it! The theme of this year's festival is "Citizens."

My talk, "A Presidency in Pictures," will be based in part on my book project in progress, which studies moments of technological transformation in the history of photography through the lens of the American presidency. I was invited to speak as part of the CHF's collaboration with the Illinois Program for Research in the Humanities at the University of Illinois. Here's how the Chicago Humanities Festival describes its mission: "The Chicago Humanities Festival is devoted to making the humanities a vital and vibrant ingredient of daily life. We believe that access to cultural, artistic and educational opportunities is a necessary element for a healthy and robust civic environment." Amen to that! Not only is it a great honor to be able to speak and to represent my campus at this event, but I've heard from several folks that the CHF audiences are simply the best around. I can't wait. You can find out more about the Nov. 1 event here. Yesterday NPR ran a piece about a research project out of Northeastern University. English professor Ryan Cordell and colleagues are using data-mining technologies to track the circulation of texts in 19th century print culture in order to determine what made certain texts "go viral."

Perfect timing, because this next installment of Making Photography Matter outtakes is about a photography joke that went viral in U.S. newspapers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This outtake opened an earlier iteration of the book's preface, but after revision I never found a good home for it. I share it here (lightly edited for length) because it's a great example of the kind of 19th century "virality" Cordell and his colleagues are interested in. And because this viral joke about photography tells us a lot about the public's anxieties about photography during this period. Let us begin with a short story about viewers and photographs. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the following narrative circulated in several American magazines: A bright ten-year-old girl, whose father is addicted to amateur photography, attended a trial at court the other day for the first time. This was her account of the judge’s charge: “The judge made a long speech to the jury of twelve men, and then sent them off into a little dark room to develop." [i] This humorous gem must have resonated with the public (or at least with magazine editors or syndicators), because nearly exact versions of it circulated in American magazines over a span of more than fifteen years; at least nine iterations were published between 1891 and 1907. [ii] While in some cases the details are different (in some versions the girl is a boy and the father is an older sister), certain features remain remarkably consistent across versions. The child lives in a house where there is a photography enthusiast; the child visits a courtroom for the first time; the judge makes a speech to the jury; and the child later recounts the experience via the punch line, which in every version I found is exactly the same: “The judge made a long speech to the jury of twelve men, and then sent them off into a little dark room to develop.” As with most jokes, the humor is found in the mistake of the protagonist. Presumably because photography is such a dominant presence in her life, the little girl draws skewed analogies. According to the child, the judge exposes the jury to a “long speech,” perhaps analogous to the timed exposure of film in a camera. Then, jury members sequester themselves in a “little dark room” to “develop” their verdict, ostensibly just as her father does the exposed film. Presumably, the “addicted” father is addicted enough to have a home darkroom, but perhaps the girl’s recounting of how the judge “sent [the jury] off” refers to the practice in early snapshot photography of mailing exposed film to Kodak for developing. [iii] In any case, the point (and the humor) of the narrative is that the little girl is doomed by being so embedded in her visual culture: she can speak only with a photographic rhetoric. Situating the story historically, it is easy see why it would have resonated with audiences. Though naïve, the little girl was not unusual in her conflation of photography with other practices of public life. Indeed, most readers of the story would scarcely remember a time when photography did not exist. The photograph, which appeared in 1839 as a unique, non-reproducible object, was by the end of its first fifty years endlessly reproducible as an artifact of mass culture. The photographer, who in the early 1840s was as much a chemist as a businessperson, had by the 1890s become also an artist, a journalist, and, evident in the story above, an amateur hobbyist. Public circulation of photographs also changed dramatically during this period. Until the late 1880s, photographs had to be transformed into engravings in order to be circulated in mass media. But the invention of the halftone process enabled magazine and newspaper publishers to bring photographs more directly to readers. The 1890s brought the “dime magazine revolution,” in which publishers began to offer cheap, well-illustrated magazines at a fraction of the cost of their more expensive siblings. [iv] By the end of the nineteenth century, photographs were ubiquitous not only at home in the albums of photographs families carefully tended but also in the magazines and newspapers they read. Given this context, it should not be surprising that Americans such as the little girl in the story creatively employed photographic rhetorics, for theirs was a world in which photography very much took center stage. If the little girl’s story suggests the ubiquity of photography in the United States at the end of the nineteenth century, it also offers clues as to how Americans understood photography’s role in the culture. Jokes comment upon our everyday experiences via exaggeration, offer us recognizable characters to laugh at, and acknowledge our anxieties and fears by tapping into them in safe ways. Humor hints at broader cultural truths. That American media were still circulating the story of the little girl more than fifteen years after its first telling suggests that the story must have tapped into public anxieties about photography in palpable ways. Consider again what the little girl says in her account of the courtroom proceedings: “The judge made a long speech to the jury of twelve men, and then sent them off into a little dark room to develop.” Her association of the act of deliberation with the act of photographic developing is humorous, presumably, because it is a failed analogy. Deliberation is a rhetorical process which entails weighing evidence and considering multiple sides of the question, often with the aim of coming to a judgment or verdict. Photographic developing, on the other hand, is a chemical process; perhaps to the little girl watching her father step into the mysterious dark room it even seemed a magical one. And the products of the two processes could not be more different – in one, a verdict arrived at through careful discussion; in another, a photograph, produced through mechanical and chemical means. Recalling that after photography appeared in 1839 it was regularly referred to as “nature’s most subtle pencil,” the “mirror with a memory,” and described as “the sworn witness to everything in her view,” there would seem to be nothing especially deliberative about it. [v] Thus the story mocks the mistake of the little girl, who falsely equates the act of producing evidence (a photograph) with the act of judgment. And yet. A deeper anxiety lurks in the story: if a photograph is taken to be a judgment, that is, if the photograph offers all the “proof” we need, then what is there to deliberate? The photograph would seem to obviate the need for deliberation entirely. Such questions about the seemingly self-evident nature of the photograph abounded in the late nineteenth century, particularly in the context of the legal system. Courts saw that photographs could be at once “privileged” and “potentially misleading” forms of evidence. As a result, they developed an ambivalent relationship to photography. Understood as a commentary on the dangers of a false analogy, the little girl’s story offers readers an object lesson on the proper role of the photograph in public culture: to treat mere photographs as equivalent to the judgments borne out of rational deliberation would be a dangerous thing indeed. This reading of the story allows us to treat it as a warning against giving photographs too much public power. Certainly such warnings circulated at the turn of the twentieth century and, indeed, still circulate today. But I want to push on the story a bit further still. What if, instead of dismissing the girl’s analogy as false and, well, childish, we take seriously for a moment the idea that she might in fact be correct? What if the deliberations of a jury are akin to developing film in a darkroom? What if photographs really are a lot like judgments? In short, what if the little girl’s mistake is not really a mistake at all? According to the little girl, the judge sends the jury “off into a little dark room to develop.” What happens in a darkroom, exactly? Certainly things mechanical and chemical and seemingly magical. But does not deliberation also play a role? However much the denotative features of photographs, in Barthes’ terms, mask their connotative ones, any photograph is nevertheless a product of countless choices, deliberations, and calculations made in and before entering the darkroom. While photographs are figured as powerful and perhaps even dangerous images that seem to bypass the need for deliberation by the authority of their realism, this second reading suggests that photographs are just like the judgments emerging from the jury room. They too are the human products of deliberation, with only so much authority as that of their producers and only so much influence as their viewers allow. Perhaps the anxiety the joke taps into, then, is not that photographs dangerously bypass deliberation, but that they decidedly don’t. Neither authoritatively chemical, mechanical, or magical, photographs, it turns out, are just as contingent as any other mode of communication. Americans during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century had to negotiate that contingency of the photograph and, in doing so, needed to constitute themselves as public agents of photographic interpretation. Notes [i] "A Bright Ten-Year-Old Girl,” Christian Union, 11 June 1891, 792. [ii] “Bits of Fun,” Outlook 2 Nov. 1895, 734; “Young Philosophers: Sayings of the Children,” Current Literature, Jan. 1897, 64; “Odds and Ends,” New York Observer and Chronicle, Dec. 1, 1898, 751; “Wise and Otherwise,” Christian Advocate, Sept. 14, 1899, 1481; “A Bright Ten-Year Old Girl,” Life, Apr. 19, 1906, 500; “In Camera,” Harper’s Weekly, Mar. 17, 1906, 383; “Odds and Ends,” Lippincott’s Magazine, May 24, 1906, 687; “A Bright Ten-Year-Old Girl,” Town and Country, Mar. 16, 1907, 95. [iii] Michael L. Carlebach, American Photojournalism Comes of Age (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997), 18-19. An earlier invention of Eastman’s, roll film, made the first Kodak cameras possible. The consumer would expose the roll of film, then mail the entire camera back to Kodak. The company would process the film and print its photographs, then send the photographs as well as a camera re-loaded with film back to the consumer. [iv] Frank Luther Mott, A History of American Magazines, Volume 3: 1865-1885 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967), 6. [v] See, respectively, D.F. Arago, “Report,” in Classic Essays on Photography, ed. Alan Trachtenberg (Stony Creek, CT: Leete's Island Books, 1980),18; Oliver Wendell Holmes, “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph," in Classic Essays, 74; and Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, “Photography,” in Classic Essays, 65. I have a habit of writing vignettes. When you're a critic who works intertextually, you tend to collect lots of "stuff" -- "stuff" being my fancy technical term for primary source materials to be analyzed or used to contextualize other data. But I confess that sometimes I get a little too enamored of my stuff. I find some little gem of historical discourse and it's just so engaging that I have to write about it. While some of these "stay in the picture," as the old time Hollywood director might say, others get left on the cutting room floor. It's not that these vignettes aren't interesting, or aren't pertinent to the larger project I'm working on. It's just that their stuff isn't quite the main stuff of the project. Still, even though they may get cut out of the book, I can't entirely get rid of them. They're too interesting! (At least to me.)

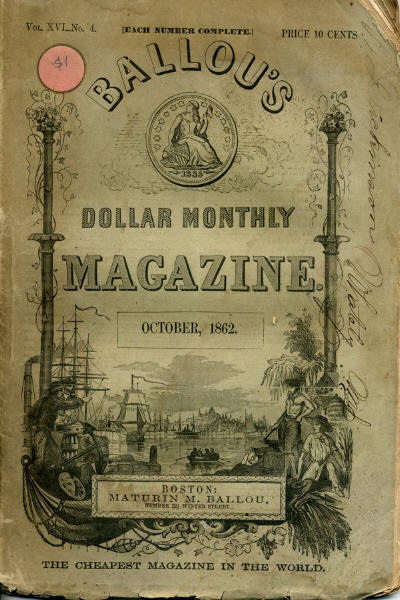

So I thought it might be fun over the next few weeks to share a couple of lightly edited outtakes from Making Photography Matter. This first one comes from Chapter One, where I show how viewers of Civil War and spirit photography in the 1860s engaged with photography during a period of national trauma and suffering. (Loosely defined, spirit photography was the practice of making photographs that purported to include in the frame the ghostly image of a dead relative or friend.) Spirit photography was "revealed" to the public in the fall of 1862 through a series of newspaper articles in Boston. While doing research for my chapter, I came across a short story that nicely illustrated how popular fiction writers of the day saw the commercial possibilities of spirit photography almost immediately. Indeed, by January 1863, the writer of the short story I analyze below had already mobilized his imagination to concoct a criminal tale of photographic mystery... “I have recently been an actor in certain scenes of an extraordinary and startling character.” So begins “The Mysterious Occurrences in East Houston Street, N.Y.,” a short story by Francis A. Durivage published in Ballou’s Dollar Monthly in January 1863. When we meet the narrator, Philip Latham, he is working as a photographer in New York City, a trade he took up after losing his fiancée in a tragic boat accident. Reporting a grief and depression that plunged him into “paroxysms of despair” and which rendered him “insensible,” Latham tells the reader that he set himself up in the photography business in order to move past his grief and help others. He explicitly links his choice to the war: “The war had broken out, and I resolved to employ my skill without charge in behalf of the gallant volunteers and their families and friends.” The grieving young man finds he enjoys making photographic portraits and he offers free portraits to two neighbors—one a young fellow named Welford and the other an elderly man. The younger man initially refuses to be photographed, but the elderly man agrees and Latham produces a portrait of which he is proud. Shortly thereafter, Latham hears a commotion outside and learns that the old man has been murdered in the night. No murderer or motive is discovered and the identity of the old man’s killer remains a mystery. Meanwhile, the younger neighbor finally agrees to sit for Latham. When Latham completes the print, he inspects it and is shocked to discover something else in the picture: hovering above Welford in the portrait is the figure of the old man, “with one hand pointing to the ghastly wound in his throat, the other designating his murderer!” Upon seeing the photograph, Welford confesses. A spirit photograph has exposed his crime. The story may best be understood as a popular attempt to capitalize on the growing public conversation about spirit photography. In writing this tale, author Francis Durivage uses the news of spirit photography to imagine the possibilities of recognition that might be contained in such a photograph: that a dead man could finger his own murderer so decisively and dramatically would be the ultimate recognition, to be sure. But the story is of interest for other reasons as well. It combines the themes of grief, war, and spirit photography in ways that anticipate later critiques of spirit photography. Indeed, grief takes center stage in the story. First, it leads the narrator Latham to launch a photography career, where he finds he enjoys helping those who wish to use photography to make loved ones far away at war more present. Indeed, the war itself hovers like a ghost over the whole narrative. On his very first day in business, he tells the reader, he photographed a soldier and his family. Realizing that they were not able to pay him, he offered his services and images to the grateful family for free. Latham explains that he learned through his photographic work “of many cases of domestic sorrow and affliction” which “taught me that I was not alone in my bereavement, and that heroism of endurance was not an uncommon virtue.”Knowing that he was not alone in his grief, that his wartime patrons also suffered untold grief and trauma, enabled Latham to empathize and to heal. Finally, Latham receives technical criticism that anticipates real-life challenges to spirit photography. After the murderer is exposed, naysayers claim that Latham must have used some technical means to insert the image of the old man into the photograph. Latham counters that he behaved honorably and is telling the truth about his experience: the ghost of the murdered man is real and his story is not the result of a “grief-maddened brain." While hardly a masterpiece of literature, Durivage’s “A Mysterious Occurrence” constituted a fascinating response to the new practice of spirit photography, offering a public meditation on the relationships among war, grief, and photographic representation. Notes: Francis A. Durivage, “The Mysterious Occurrences in East Houston Street, N.Y.,” Ballou’s Dollar Monthly, January 1863, 28 and following. American Periodicals Series database. About a dozen years ago I was helping my mom with something in the basement when I asked her about the wedding portraits. Two very large photographs of each of my great-grandparents had hung in the basement since my grandma went into the nursing home, their ornate nineteenth-century frames clashing madly with the room's plywood walls. "Have you thought about what you'll do with these?" I asked, my scholar's eye snapping into focus. "They really should be preserved." My mom nodded, adding, "You know the secret of these, don't you?" "What?" I asked. (We are not a family with very many secrets.) "Their heads were put on other people's bodies."

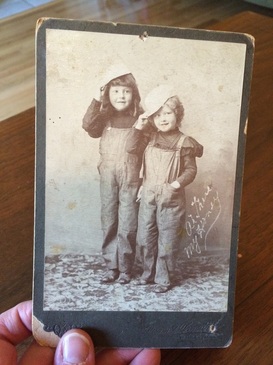

My eyes got wide and I looked at the images anew: overpainting. Of course! A common practice of the late nineteenth century where the photographed heads of customers were superimposed on other bodies (usually better-dressed ones) in a kind of early Photoshop manuever. Overpainting allowed people like my great-grandparents, newly-married in the late 1880s, to make themselves look a little better than they were, to communicate their aspirations visually. I wrote about these portraits when I started working on the article that would eventually become chapter two of Making Photography Matter. They are perfect examples of how by the late nineteenth century, the perceived relationship between photographic portraiture and human character was so implicitly well-understood that even a young couple just starting out in Kilbourne City, Wisconsin knew the score. The Finnegan family archive came in handy again in chapter three, which examines how visual fictions of childhood structured the debate about child labor in the U.S. The chapter opens with the cabinet card above, featuring my grandmother, Isabel Chase Finnegan (left) and her sister, Edna Chase Lewis. (Their parents are the ones in the wedding portraits.) Here's what I say about this image in the book: Undated but likely made at the turn of the century in a northern Minnesota frontier town, the studio portrait finds the Chase sisters engaged in a bit of cross-dressing and role-playing. Isabel and Edna are dressed identically in dark blouses and overalls, white caps placed jauntily at an angle on heads full of carefully tended ringlets. . . . Their costumed bodies offer the viewer two beloved little girls playing dress-up, masquerading to the camera as happy little worker boys. Clearly no one is fooling anyone; one would never mistake these girls for the laborers whose costumes they have put on. Not child laborers but children dressed as laborers, in this portrait the Chase girls are playfully yet squarely positioned within the sentimental frame of the sacred child (Making Photography Matter, p. 83). Later in the chapter I contrast this family image with a photograph of actual child laborers made in a photographic studio not unlike the one in which the Chase girls were photographed. Titled "A Bit of Realism," this second photograph was published in American Federationist magazine in 1902. Featuring anti-child labor activist and writer Irene Ashby-Macfayden posing maternally with three barefoot child laborers, the image appropriates "the formal, familial setting of the conventional portrait studio" in order to challenge the magazine's readers to "see child laborers as valuable, significant, and worthy" (p. 97). Without the repeated circulation of visual fictions like those performed by my grandmother and her sister, this activist image would likely have made little sense to audiences. As it was, it served as a powerful reminder that not all children got to merely play at labor. How do family photos function as photo history? For me, what makes them powerful is that, when properly contextualized within the history of the medium, they serve as concrete illustrations of changing social and cultural practices and norms, providing an almost embodied insight into the ways we make photography matter. Here, I can say. This is my grandmother as a child. I remember her as an old woman, working in her garden, and I used to sit on her lap. Yet I can also say, my grandmother and her sister represent a way of seeing children that had a powerful rhetorical impact in its time. That matters to me too. During a Q&A at a conference at Syracuse University several years ago, the ever-astute Angela Ray asked me a question that crystallized the main challenges I was facing in the project that eventually became Making Photography Matter. "So is it fair to say that what you're doing," she asked from the back of the room, "is trying to write a history of viewership?"

Whoa. Yes, I said. I hadn't had the words for it before, but yes. That's exactly what I was trying to do. That question, and the years of thinking and writing that followed, helped me recognize that the project I'd rather accidentally bumped into was implicitly driven by a key methodological challenge: How do we understand how historical viewers viewed, when they aren't around to ask? In Making Photography Matter I use my training as a rhetoric scholar to write a rhetorical history of viewership through close study of newspaper and magazine articles, letters to the editor, trial testimony, books, speeches, and comments left at a photography exhibit. I argue there that "it is within these documented moments of engagement that we may come to understand the complex and historically specific relationships that develop between viewers and photographs, and between viewers and their public world." But I often get asked this question: what about contemporary viewers? How might one go about studying how today's viewers view? One approach certainly could mirror the history I write in Making Photography Matter by analyzing the rhetorical texts produced by viewers. But when you have living witnesses, other approaches become available. You could simply ask them what they think about what they see, as Catherine Lutz and Jane Collins did in their classic Reading National Geographic. Or you could observe them, as Thomas Struth has done with his compelling photographs of museum visitors. Recently I've begun connecting with colleagues on my campus doing eyetracking research, projects in which researchers measure eye movements in order to understand better how viewers visually consume an image or a text. On my campus right now, researchers are using eyetracking to understand second-language acquisition, how the brain makes meaning, how students learn physics, and how people drive and fly planes. Closer to my home field of Communication, researchers are starting to do this work with contemporary photojournalism. This recent project funded by the National Press Photographers Association combines eyetracking research with surveys and interviews to understand what viewers think makes a compelling news photograph. I've often thought it would be fun to see what eyetracking reveals about how contemporary viewers consume historical photographs: how do our eyes make sense of images whose contexts of production and circulation may be removed from us by time and place? Making Photography Matter will be published in hardcover and available for download as an e-book after May 15. In the meantime, you can check out a 15-page preview of the e-book here. The proofs of Making Photography Matter are being finalized as I write this, and at the end of next week I'm meeting with the marketing folks at University of Illinois Press to discuss the book's May publication. This book feels like it took such a long time to appear. There are a whole host of reasons for that, including the fact that guess what? Life happens while you're writing books! But it's also the case that this book started out as one thing and then became something else entirely. I'll let my 2007 self explain, as I put it in my blog first efforts during my sabbatical year at Vanderbilt University:

ka-BOOM!The sound you just heard is the sound of my book blowing up. Thanks to two really useful seminar sessions with my fellow fellows, over the past week or so the project has exploded in scary, messy, and (I hope) potentially compelling ways. I have sensed for a while (but not wanted to accept) that I need to add an entirely new chapter as a kind of "prequel" to the time period I'm discussing (1890s to 1930s). After today's discussion I'm convinced that this is absolutely necessary. I'm also more convinced than ever that this is as much a book about deliberation, judgment, and agency as it is a book about photography. Which feels very, very right to me. Guess this is what sabbatical is for. I was lucky to have that sabbatical year at the Robert Penn Warren Center in Nashville. It made me smarter. It made me think bigger. And it made me more tolerant of ambiguity. And now, finally, the scary mess that emerged from that productive year of thinking and talking and writing has, I hope, been wrestled/cajoled/loved/worked/reworked into something compelling about photography and agency. |

ABOUTResearch news, commentary on visual politics, and a few old blog posts given new life. Archives

January 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed