|

I have a habit of writing vignettes. When you're a critic who works intertextually, you tend to collect lots of "stuff" -- "stuff" being my fancy technical term for primary source materials to be analyzed or used to contextualize other data. But I confess that sometimes I get a little too enamored of my stuff. I find some little gem of historical discourse and it's just so engaging that I have to write about it. While some of these "stay in the picture," as the old time Hollywood director might say, others get left on the cutting room floor. It's not that these vignettes aren't interesting, or aren't pertinent to the larger project I'm working on. It's just that their stuff isn't quite the main stuff of the project. Still, even though they may get cut out of the book, I can't entirely get rid of them. They're too interesting! (At least to me.)

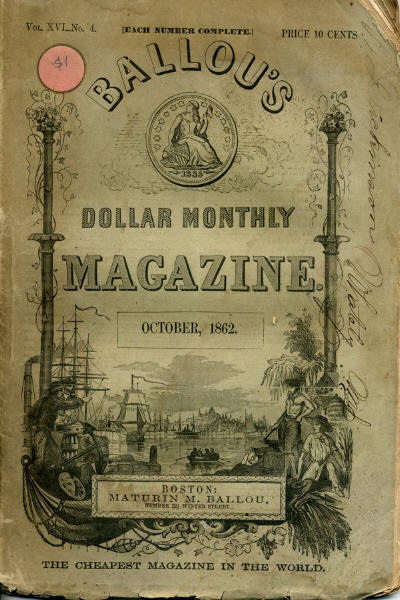

So I thought it might be fun over the next few weeks to share a couple of lightly edited outtakes from Making Photography Matter. This first one comes from Chapter One, where I show how viewers of Civil War and spirit photography in the 1860s engaged with photography during a period of national trauma and suffering. (Loosely defined, spirit photography was the practice of making photographs that purported to include in the frame the ghostly image of a dead relative or friend.) Spirit photography was "revealed" to the public in the fall of 1862 through a series of newspaper articles in Boston. While doing research for my chapter, I came across a short story that nicely illustrated how popular fiction writers of the day saw the commercial possibilities of spirit photography almost immediately. Indeed, by January 1863, the writer of the short story I analyze below had already mobilized his imagination to concoct a criminal tale of photographic mystery... “I have recently been an actor in certain scenes of an extraordinary and startling character.” So begins “The Mysterious Occurrences in East Houston Street, N.Y.,” a short story by Francis A. Durivage published in Ballou’s Dollar Monthly in January 1863. When we meet the narrator, Philip Latham, he is working as a photographer in New York City, a trade he took up after losing his fiancée in a tragic boat accident. Reporting a grief and depression that plunged him into “paroxysms of despair” and which rendered him “insensible,” Latham tells the reader that he set himself up in the photography business in order to move past his grief and help others. He explicitly links his choice to the war: “The war had broken out, and I resolved to employ my skill without charge in behalf of the gallant volunteers and their families and friends.” The grieving young man finds he enjoys making photographic portraits and he offers free portraits to two neighbors—one a young fellow named Welford and the other an elderly man. The younger man initially refuses to be photographed, but the elderly man agrees and Latham produces a portrait of which he is proud. Shortly thereafter, Latham hears a commotion outside and learns that the old man has been murdered in the night. No murderer or motive is discovered and the identity of the old man’s killer remains a mystery. Meanwhile, the younger neighbor finally agrees to sit for Latham. When Latham completes the print, he inspects it and is shocked to discover something else in the picture: hovering above Welford in the portrait is the figure of the old man, “with one hand pointing to the ghastly wound in his throat, the other designating his murderer!” Upon seeing the photograph, Welford confesses. A spirit photograph has exposed his crime. The story may best be understood as a popular attempt to capitalize on the growing public conversation about spirit photography. In writing this tale, author Francis Durivage uses the news of spirit photography to imagine the possibilities of recognition that might be contained in such a photograph: that a dead man could finger his own murderer so decisively and dramatically would be the ultimate recognition, to be sure. But the story is of interest for other reasons as well. It combines the themes of grief, war, and spirit photography in ways that anticipate later critiques of spirit photography. Indeed, grief takes center stage in the story. First, it leads the narrator Latham to launch a photography career, where he finds he enjoys helping those who wish to use photography to make loved ones far away at war more present. Indeed, the war itself hovers like a ghost over the whole narrative. On his very first day in business, he tells the reader, he photographed a soldier and his family. Realizing that they were not able to pay him, he offered his services and images to the grateful family for free. Latham explains that he learned through his photographic work “of many cases of domestic sorrow and affliction” which “taught me that I was not alone in my bereavement, and that heroism of endurance was not an uncommon virtue.”Knowing that he was not alone in his grief, that his wartime patrons also suffered untold grief and trauma, enabled Latham to empathize and to heal. Finally, Latham receives technical criticism that anticipates real-life challenges to spirit photography. After the murderer is exposed, naysayers claim that Latham must have used some technical means to insert the image of the old man into the photograph. Latham counters that he behaved honorably and is telling the truth about his experience: the ghost of the murdered man is real and his story is not the result of a “grief-maddened brain." While hardly a masterpiece of literature, Durivage’s “A Mysterious Occurrence” constituted a fascinating response to the new practice of spirit photography, offering a public meditation on the relationships among war, grief, and photographic representation. Notes: Francis A. Durivage, “The Mysterious Occurrences in East Houston Street, N.Y.,” Ballou’s Dollar Monthly, January 1863, 28 and following. American Periodicals Series database.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

ABOUTResearch news, commentary on visual politics, and a few old blog posts given new life. Archives

January 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed